EWELME - A ROMANTIC VILLAGE ITS PAST AND PRESENT. ITS PEOPLE AND ITS HISTORY.

Chapter 3

THE FALL OF THE DE LA POLE FAMILY.

By 1450 the nobles' jealousy of Suffolk's influence had come to a head, and there were various plots and intrigues to deprive him of his power and cause his final ruin. He was accused of “ sundry treasons and misprisions ”, most of them absolutely unfounded. The King being unable to save Suffolk from his enemies, he was next impeached on the ground of having “treated treacherously with France ” and was sentenced to be banished from the realm for five years. But he was not after all to escape with his life for the implacable faction was thirsting for his blood. While seeking to cross to France in a small boat, he was overtaken off the coast of Dover by a “ great ship ”, seized and brought on board. On asking the name of the ship he was told “ Nicholas of the Tower ”, and on hearing this, he lost all hope and prepared himself for death: for he remembered that the astrologer Stacey had told him some years before that “ he should die a shameful death ” and warned him always “ to beware of the Towe r”.

He was next seized by the crew and put into the ship's boat where his head was brutally struck off with a rusty sword after several blows by “ one of the lewdest of the ship's company ”.

A tragic end for the King's one-time favourite, and by the impartial standards of judgment today, quite undeserved.

William de la Pole is buried in his church at Wingfield in Suffolk, a church which greatly resembles Ewelme in style.

Before the attempted escape which ended in his death, he wrote the following beautiful farewell letter to his son John, which alone should clear his name of any stain of treason.

“ The copy of a notable letter written by the Duke of Suffolk to his son, giving him therein a very good counsel ”.

(from the Paston Letters).

“ My dear and only well-beloved son,

I beseech our Lord in heaven, the Maker of all the world, to bless you, and to send you ever grace to love Him and to dread Him; to the which as far as a father may charge his child, I both charge you and pray you to set all your spirits and wits to do and to know His holy laws and commandments, by which ye shall with His great mercy, pass all the great tempests and troubles of this wretched world.

And also that weetingly ye do nothing for love nor dread of any earthly creature that should displease Him. And whereas any frailty maketh you to fall, beseech His mercy soon to call you to Him again with repentance, satisfaction, and contrition of your heart, nevermore in will to offend Him.

Secondly, next Him, above all earthly things, to be true liegeman in heart, in will, in thought, in deed, unto the King, our elder, most high, and dread Sovereign Lord, to whom both ye and I be so much bound; charging you, as father can and may, rather to die than to be the contrary, or to know anything that were against the welfare and prosperity of his most royal perity of his most royal person, but that so far as your body and life may stretch, ye live and die to defend it and to let His Highness have knowledge thereof, in all the haste ye can.

Thirdly, in the same wise, I charge you, my dear son, always as ye he bounden by the commandment of God to do, to love and to worship your lady and mother: and also that ye obey alway her commandments, and to believe her counsels and advices in all your works, the which dread not but shall be best and truest for you.

And if any other body would steer you to the contrary, to flee that counsel in any wise, for ye shall find it nought and evil.

Furthermore, as far as father may and can, I charge you in any wise to flee the company and counsel of proud men, of covetous men, and of flattering men the more especially; and mightily to withstand them, and not to draw nor to meddle with them, with all your might and power; and to draw to you, and to your company, good and virtuous men and such as be of good conversation and of truth, and by them shall ye never be deceived nor repent you of.

Moreover, never follow your own wit in any wise, but in all your works, of such folks as I write of above ask your advice and counsel, and doing thus, with the mercy of God, ye shall do right well, and live in right much worship and great heart's rest and ease.

And I will be to you, as good lord and father as mine heart can think.

And last of all, as heartily and as lovingly as ever father blessed his child on earth, I give you the Blessing of Our Lord, and of me, which in his infinite mercy increase you in all virtue and good living and that your blood may by His Grace from kindred to kindred multiply in this earth to His service, in such wise as after the departing from this wretched worlde here, ye and they may glorify Him eternally amongst His angels in Heaven.

Written of mine hand,

the day of my departing from this land,

Your true and loving father

SUFFOLK.”

(from Napier's History of Ewelme and Swyncombe).

This last letter of William de la Pole to his son is surely sufficient testimony to the integrity of his character; every word rings true to this day. It is striking evidence of the depth of his religious faith, of his loyalty to his King, and of his trust in and affection for his wife, Alice, and also of his tender care for his young son John at that time only eight years old.

John de la Pole, in later life, was destined temporarily to repair the family fortunes, largely through his mother Alice's foresight, who prudently, if somewhat unheroically, soon attached herself to the “rising sun of York”, although after her husband's death, in spite of his impeachment, Henry VI had restored to her all Suffolk's forfeited lands. In those turbulent days it was often a matter of life and death, rather than of principle, to seize the right moment for changing sides and Alice, left a widow with a young son, doubtless acted as she thought best for his protection.

She was already connected with the house of York, through her first husband, Salisbury's daughter, who married Richard Neville whose sister Cecilia was the Duke of York's wife. Soon after forsaking the Lancastrian cause she was able to arrange for her son, John, to marry Edward IV's sister, Elizabeth Plantagenet, surely the summit of her ambition, and at Edward's coronation in 1461, young John de la Pole carried the golden sceptre with the dove before the King, a privilege first granted to his father by Henry VI.

Everything seems to show that Alice, in spite of her widowhood, was still regarded as a power in the land, still able to wield considerable influence and an ally worth seeking. This estimate of her character is borne out by her appearance, for the effigy on her tomb is that of a strong and masterful personality, although serene in death.

In 1472 Margaret of Anjou seems to have been given into Alice's custody at her Castle of Wallingford, and also (most likely) at Ewelme Manor - a strange volte face for the ex-lady-in-waiting to be her former mistress' keeper, but we may suppose that passions had died down as the years passed and that their old friendship was revived in spite of bitter memories on both sides. Alice died at Ewelme Manor in 1475, at the then venerable age of 71.

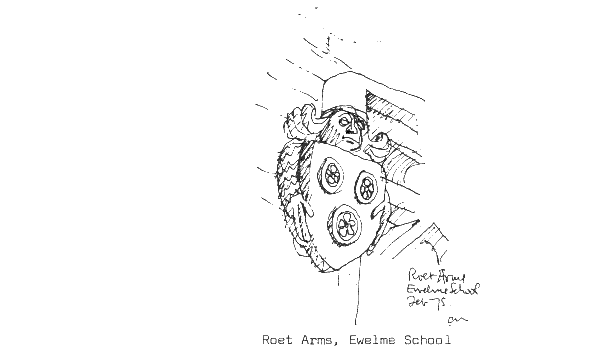

Her alabaster tomb, in St John Baptist's Chapel, is a marvel of beautiful workmanship, the gilding and colouring on the shields borne by the attendant angels being still brilliant today. Because of the delicate and artistic quality of the work, it has been suggested that it was carried out by Italian craftsmen, possibly even by the great Torregiano, who designed Henry VII's tomb in Westminster Abbey.

Alice must have been thankful to be able to end her days in peace at her old home, Ewelme Manor, full of happier memories of her early days. Fortunately she was unable to foresee the complete ruin and extinction of the de la Pole family in less than fifty years after her death.

John, Duke of Suffolk, her son, seems to have escaped the family doom, and after prosperity in early life to have died a natural death, though his later years were troubled by Henry VII's jealousy of the Yorkist noble's influence, and by his son, John, Earl of Lincoln's part in the rebellion of Lambert Simnel, and his death at the battle of Stoke, which gave Henry the opportunity, by a Bill of Attainder, to confiscate most of the Suffolk possessions, including the Manor of Ewelme. Early in his reign, however, Henry had visited John de la Pole at Ewelme, in order to allay suspicions of enmity towards the de la Pole family. John de la Pole the elder died in 1491 - a disappointed man.

His second son, Edmund, succeeded to the empty title of Duke of Suffolk, most of his lands being still confiscate. Henry, however, restored some of the lost Manors to Edmund, on condition that his estate be reduced from that of Duke to that of Earl. He is thus henceforth known as Earl of Suffolk and had the doubtful privilege of also entertaining Henry at Ewelme Manor, which after Edmund's downfall, became a Royal Palace.

The King was given the excuse he looked for to complete the ruin of the de la Pole family, for Edmund de la Pole, was shortly afterwards guilty of the “ rash and unprovoked murder of a mean man in his rage and fury ”. Suffolk fled to Burgundy to escape punishment, where he was welcomed by the Yorkist Duchess Margaret. Henry then outlawed Edmund and his brother, Richard, who seems to have been a rolling stone. John's only daughter, Anne de la Pole, became a nun at the Minories in London, and so the next generation was left without issue.

The unfortunate Edmund de la Pole, after wandering abroad for some years, sought Ferdinand of Spain's protection, by whom he was given up to Henry VII, on condition that his life he spared. This promise Henry fulfilled on the letter, but hardly in the spirit, as it is said that on his deathbed he left directions to his son to behead the Earl of Suffolk. And this behest Henry VIII was only too willing to perform, being jealous of Edmund's near kinship to the crown, through both York and Plantagenet blood. So Edmund de la Pole was executed in the Tower in 1513.

The last remaining de la Pole, Richard, who was outlawed at the same time as his brother Edmund, became a wanderer in Europe and gained a certain reputation as a Lanzknecht Captain, selling his military prowess to France and other European powers, and finally met his death fighting for Francis I of France at the Battle of Pavia in 1523. Because of his connection with the Royal House of York, he was known as “ Suffolk, dit Blanche Rose ”, and in the Taylorian Gallery at Oxford, there is a contemporary painting of the Battle of Pavia in which Richard de la Pole is represented in full armour, lying mortally wounded, his horse having fallen under him, while on a scroll over his head is inscribed his title - “ Le duc de Susfoc, dit Blanche Rose ”.

And so we take leave of the de la Pole family and their long connection with Ewelme. They were a singularly ill-fated dynasty, who during the two hundred years of their prominence in history, were always dogged by misfortune even in the days of their greatest prosperity,

Could it be perhaps that Alice de la Pole's ambition for her son had brought a Nemesis on her descendants?...For it is said by the old chronicler of Alice that “ she could not bid farewell to all her greatness without regret ”.

- I. Introduction, Origins and Early History.

- II. The Rise of the Chaucer and de la Pole Families.

- Appendix to chapter III The strange history of Jane de la Pole

- IV. Ewelme Under the Tudors.

- V. Ewelme Under the Stuarts, During the Civil War, Commonwealth and Restoration.

- VI. Ewelme from the Restoration to the Present Day.

- VII. Ewelme Church, Almshouses and School.

- VIII. Characters in the Cloisters and Village Worthies.

- IX. Concerning Old Nancy, the Gypsy.

- X. Ghosts, Fairies, the Witch, Village Tragedies and Curious Customs.

- EPILOGUE - The Pageant.